Why Americans Choose Bwindi, Mgahinga, and Volcanoes Over the Museum: Seeking the Real Mountain Gorilla Experience

The Emotional Pull of the Wild Over Glass and Diorama

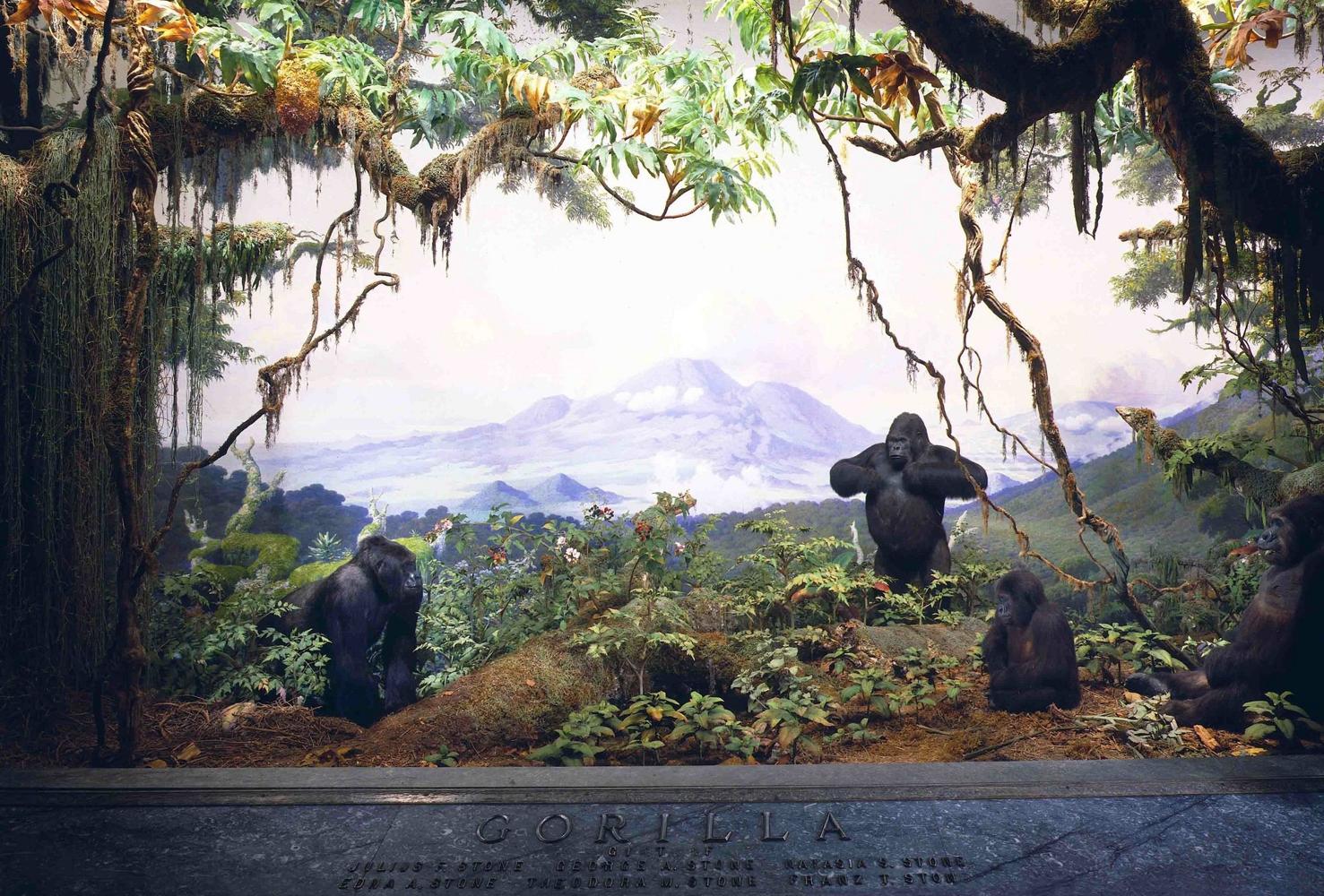

Why Americans Choose Bwindi, Mgahinga, and Volcanoes Over the Museum — For many Americans, the idea of seeing a gorilla once meant standing in the hushed, climate-controlled halls of the American Museum of Natural History, where Carl Akeley’s iconic dioramas have frozen a family of gorillas in time. It’s a powerful visual—majestic silverbacks posed in lifelike stillness among fabricated foliage. But no matter how skillful the taxidermy or how reverent the lighting, nothing in a museum can ever match the feeling of locking eyes with a living, breathing mountain gorilla in the wild. This is why more Americans are packing their bags and flying halfway across the world—not to look at history behind glass, but to step into it, deep in the green lungs of Africa.

Travelers are choosing the misty slopes of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in Uganda, the volcanic ridges of Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, and the rainforest cloaks of Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda. They’re drawn not by the convenience of proximity, but by the promise of transformation—because a real gorilla encounter in these parks isn’t just a tourist activity. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime emotional awakening.

A Living Tapestry of Behavior, Emotion, and the Unexpected

What makes seeing mountain gorillas in Bwindi, Mgahinga, or Volcanoes so utterly captivating is that you aren’t simply watching them—you are sharing space with them, in their natural, untouched habitat. When you stand mere feet away from a mother cradling her infant, or hear the low grumble of a silverback echo through a tangle of vines and bamboo, something stirs in you that no museum exhibit can replicate. This is raw, unpredictable, unscripted life.

Unlike their cousins in captivity, wild mountain gorillas don’t perform for anyone. Their movements are entirely their own. They forage when they choose, groom each other in spontaneous social rituals, and sometimes walk right past you with quiet dignity as if to say, You’re the visitor here. That moment—brief, breathtaking, and completely real—is why Americans are trading exhibit halls for elevation maps and trekking boots.

Every trek is different. Sometimes the gorillas are high up the mountainside, their silhouettes cloaked in mist. Other times they are feeding in a sunlit clearing, the air thick with the scent of wild celery. No guidebook can predict what you’ll see, and that unpredictability is part of the thrill. You are not consuming an experience—you are earning it, step by muddy step, heartbeat by racing heartbeat.

The Shared DNA of Three Parks—and Why That’s a Gift

It’s true: the gorillas in Bwindi, Mgahinga, and Volcanoes National Park all belong to the same subspecies—Gorilla beringei beringei, the rare and endangered mountain gorilla. For some, this raises the question: Why visit all three if the gorillas are the same? But that’s like asking why someone would hike the Rockies after climbing the Alps. It’s not the what that changes. It’s the how, the where, and the intimate details of the experience.

In Bwindi, the terrain is dense and mysterious. The jungle almost swallows sound, and the steep climbs make reaching the gorillas feel like a true pilgrimage. It’s raw and primeval, with over 20 habituated gorilla families spread across four sectors, offering a high chance of an encounter and an authentic trek through one of the most biodiverse forests on Earth.

Mgahinga, though smaller, offers a different magic. Nestled in the corner of Uganda where it kisses Rwanda and the DRC, it’s where volcanoes reach into the clouds and golden monkeys share the forest with gorillas. Fewer tourists come here, and that means quieter, more personal encounters. The dramatic scenery—cone-shaped peaks and high-altitude bamboo groves—adds a cinematic backdrop to your trek, and those who visit often describe it as an undiscovered gem.

Then there’s Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda. It’s the most accessible of the three, with a polished infrastructure and deeply emotional connections to Dian Fossey’s legacy. The trek here often begins just a couple hours from Kigali, and while it might be logistically easier, it sacrifices none of the intimacy. Here, the gorillas live in a land that’s soaked in history, science, and the ongoing fight to keep them safe. You walk the same trails that Dian Fossey once patrolled, and the spirit of protection still lingers in every guide’s voice.

For an American traveler, visiting all three parks isn’t about redundancy. It’s about deepening the relationship with one of our closest relatives in the animal kingdom. Each forest offers a different chapter in the same soulful story. Each trek reveals a new layer of insight—not just about the gorillas, but about ourselves.

Why Not Just See Them at Home?

So why don’t Americans just settle for a quick trip to a zoo or museum? Why invest time, money, and energy into trekking through foreign jungles, often with uncertain weather, uneven trails, and altitude fatigue?

Because this isn’t about ease—it’s about meaning. Seeing a gorilla behind a barrier doesn’t change you. But climbing into their world, hearing the rustle before they appear, and realizing you’re sharing that moment with a creature that feels something back—that changes your heartbeat. It resets your compass. And it stays with you long after the trek ends.

Americans are waking up to this truth. They want more than a photo. They want connection. They want conservation to be something they can feel—not just support from afar. And by trekking in Bwindi, Mgahinga, or Volcanoes, they’re not just tourists. They become part of a global effort to keep mountain gorillas alive and wild.